By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

To continue with the idea of celebrating a ”Year of Vermeer” at Food for the Soul, let’s start with this master when searching for letters in art history. Images of women with letters appear throughout the body of Vermeer’s work. He searched for ways of showing people’s thoughts, so portraying his subject engaged in reading or writing correspondence was a good way to convey this elusive activity.

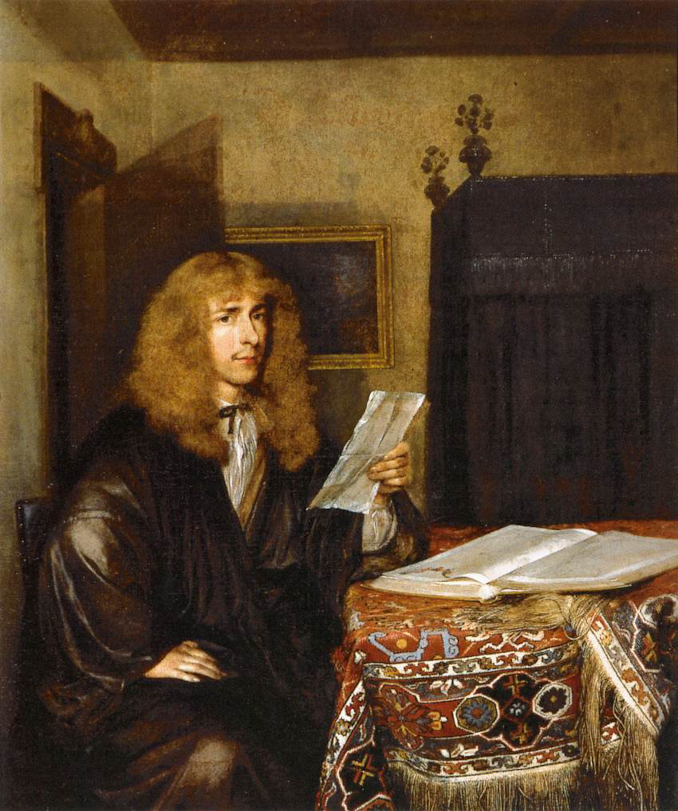

Vermeer’s earliest “letter painting” is from 1657 (Dresden, A Young Woman Reading a Letter), but the one we are looking at here is from about 1670. Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid is a beautifully crafted composition, which Vermeer painted in his mature phase of the last 10 years of his life. Like many of his paintings, it suggests a story—but it only suggests. We, the viewers, can fill in the gaps and come up with our own interpretation. A woman (wearing a cap, so she is married) is busily writing a letter. Her maid (in sensible brown clothes and wearing an apron) is standing behind her. She is not looking at her mistress; her gaze, a bit distracted, is directed at the window. Perhaps she sees something in the courtyard, or perhaps she is bored with the task of waiting for her mistress to finish the missive that will have to be given to a kitchen boy to deliver. Perhaps she has her own thoughts about this letter if, by chance, this is not an ordinary correspondence but a letter to a lover. Perhaps she disapproves? Perhaps she worries that an affair might create a break-up in the household and threaten her job stability? There are so many suppositions that we can weave while looking at this simple picture of two people in a room. The details are also exquisite—an elaborate carpet that covers the table, a crumpled paper on the floor (an earlier, failed version of the important letter?), the artist’s signature on the part of the paper hanging over the edge, a glistening pearl in the ear of the mistress.

Unlike other Vermeer canvases, this painting stayed with the artist until the end. It remained unsold at his death, and his widow gave it to a baker as payment for unpaid bills. In the 20th century, the canvas underwent a dangerous adventure. In 1974, an IRA unit led by the infamous Rose Dugdale broke into the Russborough House mansion near Dublin, stealing this picture together with 12 other famous artworks. Unlike the Vermeer stolen from Boston, this one luckily was recovered in 1993 after years of negotiation with the picture’s kidnappers.

Among the six so-called “letter paintings” by Vermeer, the most intimate and “modern” is the one entitled A Lady Writing, which graces the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. The woman is dressed in the yellow morning jacket that we know so well from other Vermeer paintings (most notably from Mistress and Maid at the Frick museum in New York). Originally, the artist painted his model holding the pen more vertically, that is, poised for writing. Eventually, he changed his mind—he did that a lot in all his paintings—because clearly, for him, painting was a process of building an image and its meaning. In the final version of this canvas, the pen is at a more relaxed angle; the woman is only holding the quill, but she is no longer writing. Instead, she is looking at us with a friendly but very direct gaze. She is the original “girl, interrupted.” There is a theory that this may be a portrait of Vermeer’s wife Catharina, and if so, it would make it an intimate portrait, the writing implements being just props. This painting is also very different from the scenes of a maid and her mistress in that this is a very carefully composed “close shot.” The process of writing may give a context for the woman’s activity, but such proximity to the model puts the focus on the person—we examine her while she is interacting with us.

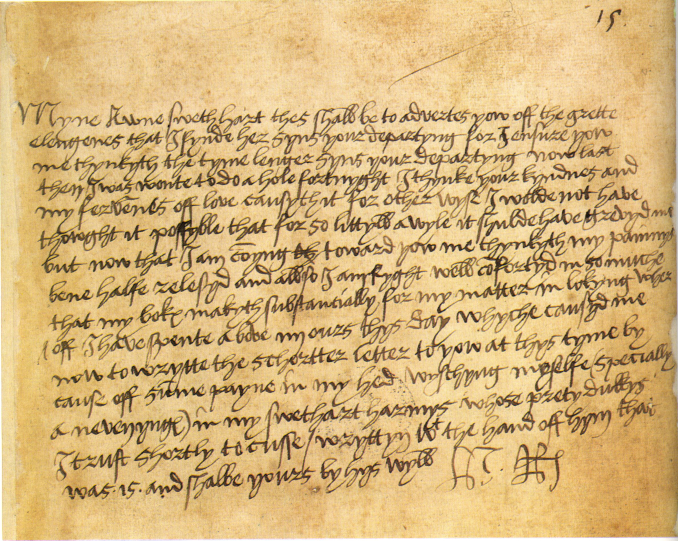

In 1527, Henry VIII was deeply in love with Anne Boleyn and longing for a male heir that the queen could not give him. He had famously sent a letter to the Vatican asking for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, by this act initiating the departure of England from the Catholic church. Pope Clement VII was at the time virtually a prisoner of the invading army of Emperor Charles V, and he was not in a position to grant such a request, not that he would have been particularly willing to aid the “rogue” king in breaking away from the Roman sphere of influence anyway.

In 1530, the king’s request was further supported by a group of English nobles who wrote to the pope threatening the Catholics in the kingdom if the request was not granted. In 2009, the Vatican archives produced a replica of the nobles’ letter—the document holds the 81 heavy wax seals of the signatories and as such weighs 2.5 kilos (about 5.5 pounds). This impressive facsimile was equally impressively priced at 50,000 euros when it was offered to archives and collectors all over the world.

Both letters—the king’s petition and the supporting letter of his courtiers—belong to some of the most famous pieces of correspondence in the history of England. Interestingly enough, the Vatican Apostolic Library also has in its possession 17 love letters from Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn.

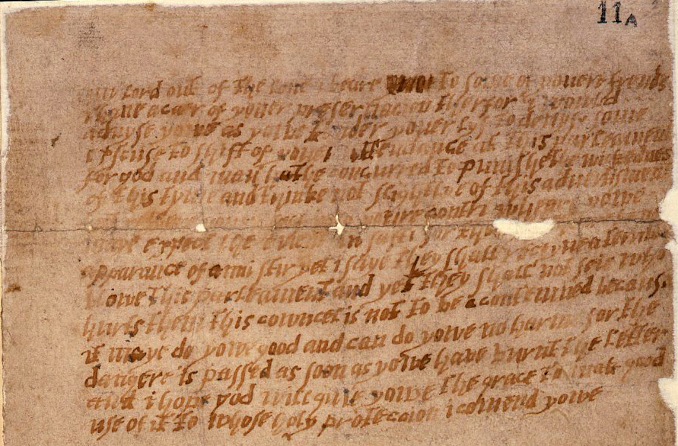

Few historical events in England hinged as much on a letter as the Gunpowder Plot in 1605. In the plan hatched by a group of Catholic nobles who were trying to restore the Catholic monarchy in England, the plotters planned to blow up the House of Lords of the Parliament and kill King James I in the process. One of the conspirators, a man called Guy Fawkes who had some military experience, was tasked with installing and igniting a series of explosives underneath the Parliament hall’s floor.

The plot was revealed, however, in an anonymous letter sent to the royal courtier Baron Monteagle, resulting in a thorough search of the Parliament building. The gunpowder was found, and the conspirators were rounded up, tortured, tried, and executed. The Protestant monarchy of King James I was preserved. The author of this letter was never revealed. Ken Follett, an eminent writer of historical fiction, included the mystery of the letter’s authorship in his 2017 novel about the period called A Column of Fire.

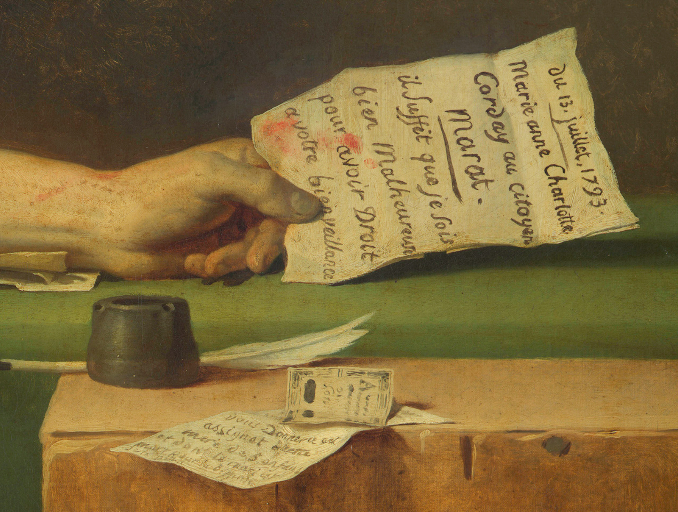

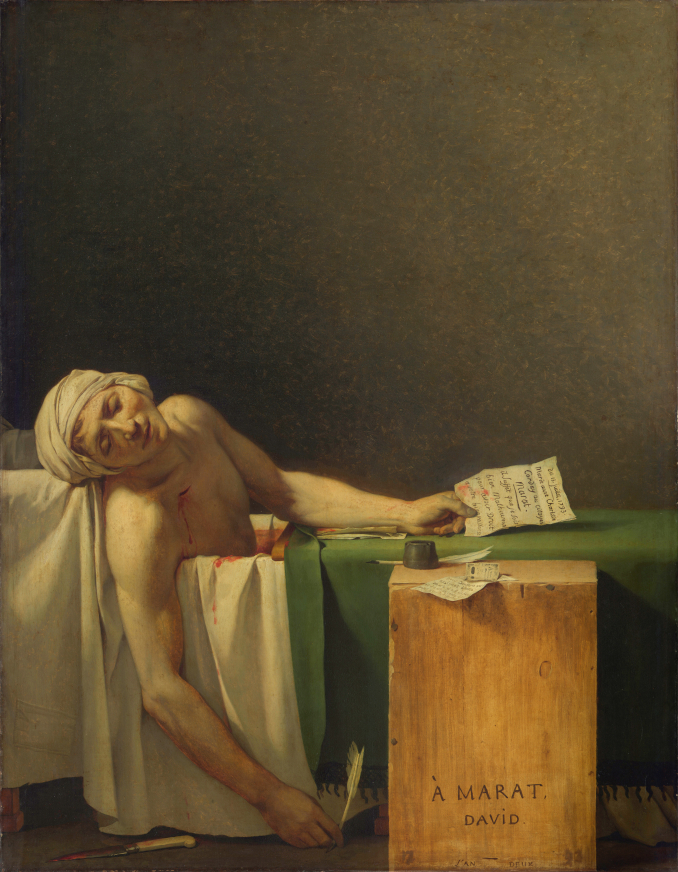

Last but not least, we can take a long look at probably the most iconic “letter painting” ever: Death of Marat painted by Jacques-Louis David in 1793, right in the middle of the French Revolution.

Jacques-Louis David was already a famous painter before the revolution, and his Oath of the Horatii was actually commissioned for the royal collection of Louis XVI. However, David’s sympathies lay with the Jacobins, and he joined the French Revolution with the same enthusiasm as the subject of this future painting, Jean-Paul Marat. During the years of the French Republic, the artist became a de facto Minister of the Arts, dismantling the Royal Academy (he was sore at them for denying him an Italian travel grant called the Prix de Rome for three years running), designing revolutionary uniforms and symbols, and staging official events. Marat, a failed scientist, found his calling in writing a political newspaper entitled L’Ami du Peuple (“The Friend of the Nation”). Both men were signatories of the death warrant of King Louis XVI.

The wheel of fortune turned, however, and a few months after the execution of the king, violent death came for Jean-Paul Marat as well. He was stabbed in his bathtub by Charlotte Corday, a young woman from the provinces who was protesting the revolution having changed into a terror.

David portrayed Marat as a victim sacrificed by a bloodthirsty revolutionary, even if in reality Marat was the one demanding the destruction of everybody, while Corday was reacting to the assassination of her family. The irony is that David later changed sides again and became a supporter of Napoleon, eventually ending in exile when the monarchy was restored in France.

But politics, like weather, is a transitory phenomenon. Let’s concentrate on art instead. It’s such a powerful picture. On the one hand, this is almost like a crime scene, with a bloodied victim leaning out of the tub. You can almost imagine a police crime scene photo, except that photography would not be invented for another 40 years, so this is as good as it gets, image-wise. On the other hand, this is an allegory of martyrdom, painted in the style of a Renaissance pietà. Marat is in a pose of the crucified Christ, pictured dramatically against a severe black background, with the lifeless body placed in a tub that resembles a Roman sarcophagus.

The art of letter-writing had its apogee in the previous few centuries where this form of communication was ubiquitous and necessary for business, social life, education, and the political life of a country. The advent of electronic communications has wiped out both business and private correspondence—hardly anyone sends physical love letters anymore, while business information travels via emails or messages, and only ominous communications are still sent in writing—legal summons, financial notifications, or firing of people from jobs.

Letters have disappeared from art as subject matter as well. Already in the 19th century, they mostly appear in genre scenes like the one above in First Love Letter, a moralistic Victorian image by minor artist Edward Quitton.

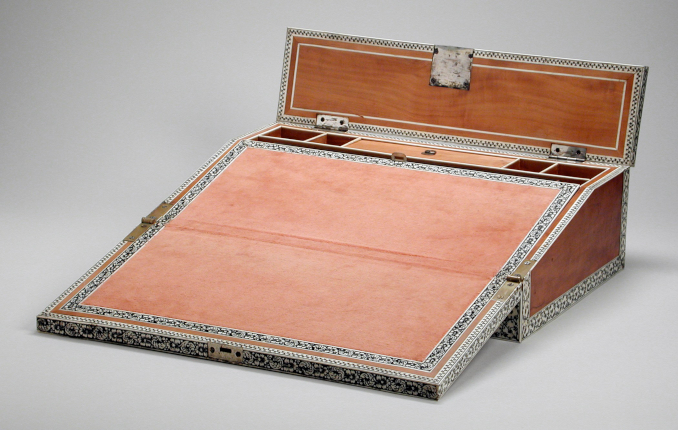

The disappearance of physical letters from mankind’s material history will be a loss to archeologists of future generations. The UK’s National Archives have in their collection such milestone letters as one from Winston Churchill to President Roosevelt requesting U.S. help against Hitler, a letter from Karl Marx applying for British citizenship, and correspondence between Clement Atlee and Harry Truman in regards to Hiroshima. There will be hardly any such letters in the future. It looks like the 21st century will mostly be recorded in text messages and social media postings. In art, letters have disappeared from iconography, and I have yet to see a painting of a Twitter posting. The demise of letter-writing also means the disappearance of writing desks, which will go the way of inkwells, paper blotters, and even pens—all being relegated henceforth to museums.